People are curious about my journey of starting a flower farm. I followed a dream which has been daring, difficult and incredibly satisfying. In this blog, I hope to share a bit about what I have learned along the way.

I have been on a long road with plants, beginning as a child in the backyard wilds of the Vermont forest. The earth knew my name and was always calling to me. I found jobs where I could be outside in the dirt and the elements. Meeting the desert plant family changed me forever. I was captivated by their spiny adaptations, how they could survive on cliffs in the sun, without leaves, and offer beauty, utility and medicine to the people. As I learned more about the natural world I wished to be in service to the protection of wild places. I studied, sketched and pressed plants as a botanist and spoke to them in their Latin names. I was taught that some plants are considered bad guys and was recruited by the government to kill the invasive trouble makers that were taking over native habitat. I gladly led armies of volunteers to beautiful, remote places to eradicate these weeds. There were millions of acres to protect and restore, but after awhile I felt like my efforts were a drop of rain on a thirsty landscape.

All this time I had always been a gardener, wherever I lived for however short a time. I planted seeds and grew food and created little pockets of native habitat in backyards. When I reached midlife and realized I had less time ahead of me than what was behind. I started to get serious about how I spent my time, and wanted to organize my life around what I love. I made some big changes—left my marriage, and quit my job and started apprenticing, interning and volunteering on farms.

After thinking about it a lot one day I woke up with a new dream to be a farmer. There is a freedom to design your life at the intersection between your passion, your skills and what the world needs most. I would be able to be around plants all the time and be growing them—not killing or studying them. I would wake up on the farm and not have to go into the “field” as botanists refer to the place where they go to see plants. This winding, dirt road (more like a path with a few rock karins) is ultimately how I got here, to Wild Heart Farm. When I walked through the gate of this one-acre riparian woodland in the floodplain of Beaver Creek, I knew this was the place.

The farm in 2022 when things were just getting going - the land has good bones. Photo by Amy S. Martin

Every vocation has its ups and downs. The glamorous side the public sees and the sloppy, sometimes sad backstage shenanigans once the show is over. I wanted to grow flowers because they make people happy. Watching a flower grow from a seed into a gorgeous blossom that attracts butterflies and bees makes me extremely happy. Even better is to follow that flower all the way back to the beginning when it becomes a seed again. This is the closest I have ever been to witnessing real magic. And plants do it without even thinking about it. Against all odds. Again and again.

Our immediate farmily—my partner Mike and sister Kelly and our two darling dogs. Photo by Amy S. Martin

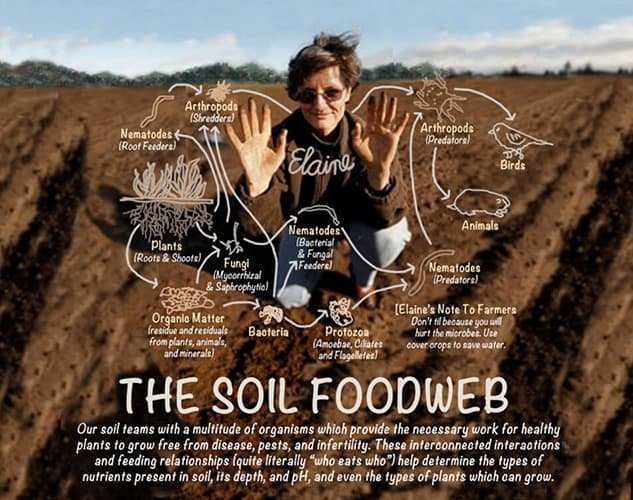

Then there is the economic sustainability of not just starting, but keeping a business thriving. How do you make a dream pencil out financially so you can pay the bills? I wanted a place where I could apply everything I learned so far about conservation, restoring ecosystems and reading the land. Then I became a farmer and wanted to grow every pretty little tasty thing I saw in catalogs. I wanted to be successful and this meant making a profit. The balance between listening to the land and production farming is a seesaw. The culture on social media feeds the machine of never being enough, there is always something new to grow, or another farm prettier than yours. I never though flowers could be anything other than a flower, but the industry refers to them as “products.” Finding time for myself and the land to rest has been difficult. At the end of every season I am more exhausted with the cumulative stress and all out stamina required to not only grow flowers but design and deliver them for very important life events.

Out foraging and exploring my backyard native plant communities is one of my favorite activities.

When I created my Wild Heart Farm haven I was really tired of patriarchy. I was sick of listening to men explain things to me. I wanted to create a place where women rule—they are the decision makers and culture keepers. I wanted to escape capitalism by starting a purpose-driven business that ran on reciprocity and yet I could barely pay myself (let alone others) minimum wage. Everywhere I turned for advice I was asked for a business plan and a greater profit margin, which means growing more, doing more, selling more. I wanted to break colonial legacies, and yet here I am a new age colonist growing flowers on stolen land. These systems are hard to uproot in oneself. For me it is an ongoing conscious effort.

The shecosystem we are part of with other women-owned businesses (chefs, chocolatiers, winemakers, potters, herbalists, earth builders, you name it!) is ever growing, and incredibly resilient. I feel like I am part of a web of goodness. I can both support and be supported. In 2021 a dozen flower farmers from across Arizona gathered at the farm to connect and share challenges and opportunities. Today there are three times that many flower farmers in our state and we are joining forces as the Arizona Flower Collective to get our local stems to florists. Running my own farm I learn new things about myself, about plants, about math; I am constantly growing and evolving. The men involved in our farm are loving and gentle. No one drives a tractor and everyone gets a turn on the broadfork. We all feed each other and are fed.

Dani and Terri are dear friends and stunt double as floral designers for our events.

There is great satisfaction in creating something bigger than yourself. In making an offering to the world with a few words, placing a dot on Google, inviting people in. Nothing happens quickly—we aren’t all zinnias ready to bloom in 80 days. We won the neighborhood over one flower bouquet at a time in the midst of the COVID pandemic. We slowly grew a community of supporters through our CSA who unflinchingly invest in our farm by purchasing shares upfront when my credit card is maxed out early in the season when there are no flowers to sell. They pump me up every month when I deliver their flowers. These are relationships that are growing and deepening. The children born into our community know this heavenly land of wonder and magic. People need flowers throughout their lives and we are here to bear witness and offer beauty and meaning.

The farm grows all of this, and hopefully as I find inspired moments there will also be more teaching, stories, songs and poems. Thank you for reading this. Feel free to share thoughts in the comments.